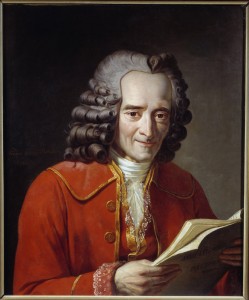

« I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it ». This maxim is wrongly-attributed to Voltaire. And it might just be what Google needs. Indeed, the current Google situation is a typical situation of Innovation vs Dogma.

Back to facts

- In the course of the summer 2017, a memo by Google employee James Damore leaks out, stating that (in short) women are biologically not meant to be engineers…

- James Damore gets fired

- Google CEO Sundai Pichar needs to cancel a company-wide interactive session about gender discrimination, after several employees complained that they would not be able to express their views without retaliation from fellow employees.

Quick disclaimer

Just to set things straight: this blog is not about opinions. However, we think it relevant to point to scientific research which prove James Damore wrong. Also, we can’t emphasize enough how women greatly contributed to science and computing. Marie Curie and Dame Stephanie Shirley are enough to ridicule the whole career achievements of James Damore.

Google wanted so much to be inclusive that it got exclusive

But back to Voltaire: an innovative company must allow anyone to feel comfortable being who they are, regardless of political opinions. The Google situation is a meaningful management lesson: Google wanted so much to be inclusive that it got exclusive.

It is hard for a company that excels so much in not paying taxes to pretend to work for the good of humanity. Kittens don’t replace schools, hospitals or roads — and these are paid by taxes. “Don’t do evil” was Google’s mantra — which Steve Jobs rightfully called “Bullshit”.

Nevertheless, from a very cynical business perspective, Google needs inclusive values, because:

- It is good for its image. When your whole business is based on spying on people, and that the NSA leverages that to get info on millions of citizens, you needs to work on how you are perceived by society.

- It promotes a culture of performance. Not matter who you are, we only value what you produce.

- It increases resources in the long term. Exclude women and your world is 50% smaller. Add to this non-caucasians, homosexuals, and republicans, and you’ll be quickly in shortage of workforce and customers.

The problem is that embracing inclusiveness may be dogmatic, when it means that alternative opinions are excluded. For example, some moderate conservatives start to feel uneasy working at Google. Being inclusive to this extent is being exclusive.

Instead, Google needs to worry about its innovation culture. It needs to make sure that inclusiveness applies to its employee’s careers. If James Damore was not valuing any woman engineer, maybe his job performance would show it. This is when communication does not replace action. James Damore may have been fired to quickly close the topic, it may actually have opened a pandora box and create a deadly fight internally to the company.

Democracy and capitalism

In order not to do evil, Google needs to learn to actually be inclusive: by paying taxes, by participating in society at large without taking part in the debate, and by enforcing performance metrics that are affected by inclusiveness. In short, accept not to be in control of everything, as long as it allowed the debate to take place. Let’s call that … democracy?